On 5 August 1914, 5 days after the outbreak of World War 1 and the day after Britain declared war on Germany, the British Government passed the Aliens Restrictions Act, whereby the British Government could control the movement of “enemy aliens”. General internment of all German and Austro-Hungarian born men of military age began in May 1915 following the sinking of the “Lusitania”.

The introduction of Aliens Restrictions Act of 1914 was initially focussed upon identifying potential spies however all "enemy aliens", even if they had lived and worked in England for many years, together with their wives (including wives who were British born but who effectively took their husband's nationality upon marriage) had to register as an “enemy alien” or face a significant £100 fine or six months imprisonment. Amongst other things, the Act restricted their travel to within a 5 mile radius.

With internment initially aimed at those thought to be a potential danger to the public, the first internees of 1914 went into hastily arranged temporary (and often unsatisfactory) camps, such as disused factories, aboard ships off the south coast or former workhouses.

The first 200 internees arrived on the Isle of Man in September 1914 for internment in Cunningham’s Camp, a former Young Men’s Holiday Camp in Douglas which had quickly emptied as war broke out. Pressure on space with overcrowding and complaints over the poor quality of the food ultimately led to a riot in Douglas camp resulting in the deaths of six internees.

With the escalation of the war and public concern over “the enemy in their midst” whipped up by the press resulting in ever increasing numbers of internments, more space was needed. In October 1914 the British Government returned to the Isle of Man and identified Knockaloe Moar farm, a former training camp for Territorial troops. The first of the civilian male internees arrived on 17 November 1914 and ultimately the internees were of various nationalities including German, Austrian and Turkish.

The critical turning point for internment was the sinking of the passenger ship Lusitania on 7 May 1915 after it was torpedoed by a German submarine. This led to serious riots initially in Liverpool and the East End of London, with German and other “alien” families being attacked and it was reluctantly agreed that “for their own safety and that of the community” all non-naturalised adult males between 17 and 55 should be interned or, if over military age, repatriated. Women and children “in suitable cases” would also be repatriated, except where in the interests of humanity they should remain. It was agreed that the estimated 8,000 naturalised aliens should not be interned unless it was deemed dangerous to leave them at large (House of Commons, 13 May 1915).

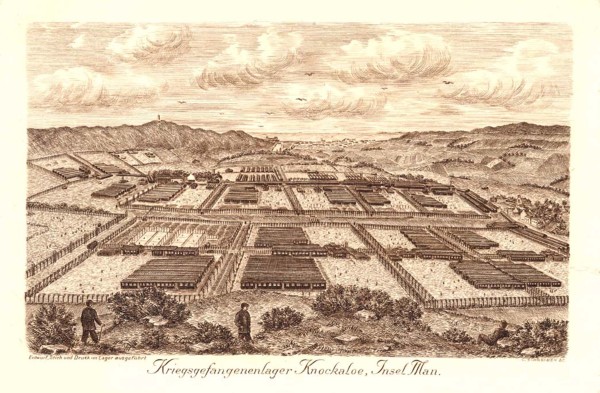

Initially anticipated to hold 5,000, following the sinking of the Lusitania it was agreed that Knockaloe, safely situated on an Island in the middle of the Irish Sea, should be expanded to house the vast majority of civilian internees held in the British Isles.

Knockaloe Camp ultimately held “nearly 24,000 prisoners in 23 compounds inside barbed wire, with 4,000 old soldiers acting as armed National Guard, and 250 civilians attending to their wants and comforts…..The camp at Knockaloe was three miles in circumference; 695 miles of barbed wire surrounded the compounds” Samuel Norris “Manx Memories and Movements”.

Knockaloe Camp became the he largest internment camp of WWI by far, and central to the British Government’s alien policy. Internees could be moved a number of times throughout the duration of the war but the vast majority of them spent some, or all, of their internment at Knockaloe. Most were not to leave until 1919.